Trying to write a bit more about older books I read, so: quick thoughts on two SF novels that could be described as cult classics that I finally got around to reading in recent months.

John Shirley, City Come A-Walkin’

I’m not sure I’ve read anything by John Shirley since my teenage years, when I picked up the anthology Mirrorshades. I picked up a used copy of City Come A-Walkin’ at Ridgewood’s Topos; it fell into the category of books I’d heard about for years but had never read. Spoiler alert: it kicked my ass.

I’ve mostly thought of Shirley as a science fiction writer, and while this novel has more than a few SF elements — a near-future setting, some technological advances relative to now — there’s also plenty of space for the fantastical in here. One major character is a kind of hegemonic consciousness of the city; it’s never really explained if this being’s origins are technological or supernatural. Shirley isn’t terribly concerned with its origins, though; instead, much of the tension of the novel involves the gulf between a godlike being and the humans it’s content to use as cannon fodder in its ongoing conflict.

Two minor details worth noting here as well: first, Shirley writes about music and musicians very well, and this is the rare novel about near-future musical subcultures that feels believable. The other is the novel’s dedication — “To every woman who ever had to put up with me” — which, as candor goes, ranks very high and possibly borders on “oversharing.”

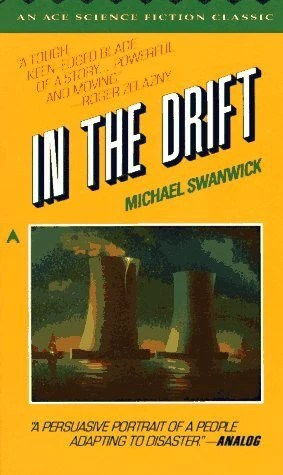

Michael Swanwick, In the Drift

It hasn’t been long since I read Tor Essentials’ new edition of Michael Swanwick’s Stations of the Tide, a novel I’d first read as an angsty teen and found myself digging considerably as an angsty middle-aged human. I ended up ordering Dover’s reprint of his first novel In the Drift, set over the course of several decades in a northeastern United States after a nuclear reactor meltdown devastated virtually everything in sight.

I wasn’t expecting quite as much crime fiction DNA to be present here as there was. One of the significant threads of this novel involves one of its central characters evolving from a wide-eyed kid to a local crimelord. (If you’ve ever wondered what a dystopian Philadelphia would be like, do I have a book for you.) I say “one of its central characters” because this feels more episodic than anything — think The Martian Chronicles, but with more racist gangsters and sympathetic vampires.

The scope of this novel is one of the bigger surprises it has in store for readers. Several of the other books of Swanwick’s I’ve read — the aforementioned Stations of the Tide and the incredible Jack Faust — have a character-focused perspective. In the Drift feints in that direction, but it’s ultimately about something bigger; that’s why its emotional beats land with such force.

Leave a comment